by Ian Mann

August 01, 2024

/ ALBUM

Some of the freshest, most stimulating and most enjoyable music that I’ve heard all year. Williamson impresses as both a writer and an instrumentalist.

John Williamson

“The Northern Sea”

(Ubuntu Music UBU0182)

John Williamson – double bass, Alex Hitchcock – tenor saxophone, Jonny Mansfield – vibraphone, Jay Davis – drums

with guests; Immy Churchill – voice, Alex Wilson – piano

“The Northern Sea” is the leadership debut of bassist and composer John Williamson, recently heard on pianist Phil Merriman’s new album release “The Roots Beneath”. Review here;

https://www.thejazzmann.com/reviews/review/phil-merriman-trio-the-roots-beneath

As the title of his own album suggests Williamson hails from the north of England, Yorkshire to be precise. He studied at The Royal Academy of Music in London where his tutors included bassist Orlando Le Fleming, pianists Nikki Iles and Kit Downes and multi-instrumentalist Jim Hart. In 2023 he received the Scott Philbrick Prize for the highest post graduate recital mark.

Williamson has also studied in Leeds and acted as bassist and musical director for the Leeds University Big Band, with whom he appeared at the North Sea Jazz Festival in Rotterdam.

Williamson also spent time in Washington DC where he worked with the saxophonist Brad Linde and guitarist Anthony Pirog amongst numerous others. He also acted as house bassist for the acclaimed Bohemian Caverns Jazz Orchestra.

Since moving to London Williamson has established himself as an in demand player on the capital’s music scene. Among those with whom he has worked are saxophonists Emma Rawicz, Sam Braysher, Alex Garnett, Matt Anderson, Rachael Cohen and Vasilis Xenopoulos, guitarists Nigel Price, Hannes Reipler and Nick Costley-White, pianists Paul Edis and Sam Leak, vocalist Jo Harrop, violinist Dominic Ingham and drummer Gene Calderazzo.

For his debut release Williamson has enlisted the services of a stellar core quartet featuring saxophonist Alex Hitchcock, drummer Jay Davis and his frequent collaborator and fellow Yorkshireman Jonny Mansfield on vibraphone. Alex Wilson plays piano on three of the eleven tracks while singer Immy Churchill adds her voice to two of these.

Williamson says of the music to be heard on “The Northern Sea”;

“The material is arranged for a variety of line-ups, from duo to full sextet, relying on the commitment and invention of the musicians to build a coherent sound. Individual influences that can be traced include Charlie Haden, Lee Konitz, Radiohead, Charles Mingus and Carla Bley, and the music encompasses a wide range of feelings and approaches. Angular post-bop (‘Contrafact 1’) sits alongside big-sky, Americana-inspired folk (‘2700 Q Street Northwest’) and anthemic contemporary jazz (title track ‘The Northern Sea’). The album is united by a ‘melody-first’ writing style. Each piece stays true to the core melodic line, whether that melody is pushing against the boundaries of a conventional harmonic structure or working as a scaffold for something more unusual.”

Williamson’s album liner notes provide further insights with regard to the individual tracks and the recording gets underway with “Contrafact 1”, of which Williamson says;

“I wrote this very quickly, late at night, trying to fit as many wrong notes as possible into a simple C-major chord structure taken from the jazz standard ‘I Should Care’.”

Appropriately the piece begins with the sound of the leader’s bass and it’s also Williamson who takes the first solo, his playing both muscular and fluent, and also highly dexterous. Precious little remains of the standard that inspired the piece as Williamson and his colleagues explore a sound-world that owes something to the music of Ornette Coleman, Charlie Haden and Eric Dolphy. The always excellent Mansfield takes the next solo on vibraphone, followed by the similarly estimable Hitchcock on tenor. Drummer Jay Davis links up strongly with Williamson and also shows up strongly in the tune’s closing stages. An exciting and invigorating start from the core quartet.

Of the next piece, “Gozo”, Williamson says;

“Like most of the album, this piece started as an isolated melodic line. After being honed on gigs and redrafted, it settled into its final form as a loose, free-sounding yet ‘through- composed’ tune — there are no solo sections, and the improvisation is instead contained in the flexible delivery of the fixed melodic content. The title refers to a dog that one of my sisters met in an animal sanctuary in Gozo, and who was eventually adopted by our parents. Rufus — for he is the dog — was hiding under a table at Saltburn Jazz Club the first time this tune was performed”.

The composer gives an accurate description of this short (two minutes) piece, which remains pleasantly melodic despite the looseness of the structure. Although there are no designated solos both Mansfield and Hitchcock assume the lead at various points.

Similarly brief is “Introduction to The Northern Sea”, played by the quartet of Williamson, Mansfield, Davis and pianist Alex Wilson. Davis ushers the piece in from the drums and guest Wilson plays a prominent role in the subsequent performance. Williamson says of this item and of the composition that follows it;

“The title track was the last to be composed, after a few months of writer’s block which I tried to escape by playing endless sequences of notes without a harmonic or structural context. One such sequence became the basis of this piece, and the intro is a nod to the ‘blank verse’ way the notes of the tune were first assembled. Rolling between three- and four-beat time signatures, a winding melody makes brief excursions in and out of the home key. The instrumentation shrinks to a piano trio, finding a chamber jazz feeling which gives way to a cathartic second section as saxophone, vibraphone and voice enter”.

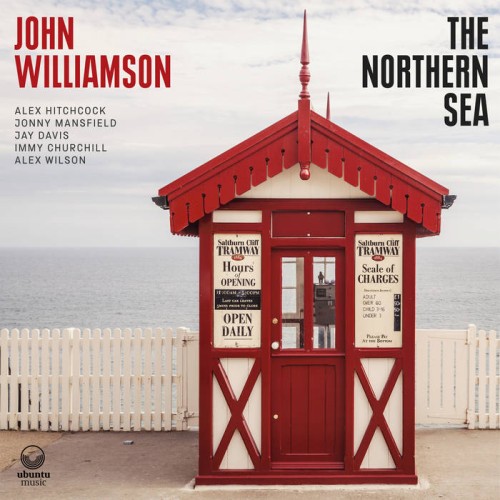

The core quartet plus Wilson are involved in the opening stages of the main piece before the guest pianist takes an inventive and expansive solo with the group now in piano trio mode. Hitchcock and Mansfield enter into a lively series of exchanges as this lively track builds up a head of steam, with Churchill adding soaring Norma Winstone like wordless vocals to the proceedings. Despite the occasional reflective moment this is essentially an upbeat piece and it’s easy to see why it was selected as a single. The title represents a celebration of looking out at the North Sea from Northern England, and presumably from Williamson’s home town of Saltburn on the North Yorkshire coast. Nico Taylor’s cover image of the ticket booth for the Saltburn Cliff Tramway provides the visual counterpart to Williamson’s music. The album package includes an aerial shot of Saltburn Pier too.

“Nothing Grows in Concrete” borrows from Sibelius’ Symphony Number 2, a work that Williamson had performed as a young violinist in the East Riding Youth Orchestra. The composer says of this short (two minutes) but beautiful composition;

“The sparse instrumentation (vibraphone, bass and drums) and austere delivery is designed to cut through the naive simplicity of the melody”. Mansfield’s vibes twinkle appealingly, while Williamson and Davis, the latter deftly and delicately deploying brushes, play with great sensitivity throughout.

Of “Contrafact 2” Williamson states;

This contrafact is loosely based on the chord sequence from the standard ‘I Can’t Believe That You’re In Love With Me’. Inspired by greats such as Lee Konitz, Warne Marsh and Lennie Tristano, I aimed to use strong, ‘singable’ gestures and motifs to sell an otherwise abstract, highly chromatic melody. This piece was originally written for the Washington DC-based saxophonist and Konitz disciple Brad Linde, with whom I played as part of his Team Players group while spending time in the US, performing compositions themed around sports”

Performed by the core quartet this is a fast moving piece centred around Williamson’s nimble and propulsive bass lines and featuring darting, bebop inspired melody lines, these forming the basis for lively solos from Mansfield and Hitchcock, these punctuated by a series of bustling drum breaks.

Of the Mingus inspired “Get Out While It’s Light” Williamson says;

“The three-part structure of this piece is inspired by Charles Mingus’ programmatic works. The opening section is based around the first melodic pattern, which appears in three places, transposed each time, and requires an unusual chord sequence that gradually becomes more ‘inside’ and traditional throughout. After Alex Hitchcock’s saxophone solo, a simmering walking bass line takes over, with exploratory improvisation from Jonny Mansfield (vibraphone), and drums growing steadily more intrusive in the build-up to a solo by Jay Davis. The piece concludes with an energetic and disorganised recapitulation of the opening section”.

Williamson also recounts that he first performed this piece in duo format with saxophonist Emma Rawicz in a practice room at the Royal Academy, the pair using the working title “Duke Ellington’s Sound of Hate”!

Again performed by the core quartet this is a haunting and beautiful piece that subtly alludes to Mingus’ roots in the blues. Hitchcock delivers a fluttering, beguiling solo, playing with great sensitivity. As Williamson has stated Mansfield takes over at the vibes before Davis’ drums become the centre of attention. Hitchcock then resumes the lead, playing more forcefully this time, in the closing section.

“Contrafact 3” is a ‘saxophone trio’ performance by Williamson, Hitchcock and Davis with Mansfield sitting out. Of this piece Williamson explains;

“The final contrafact is in a chordless trio instrumentation, allowing for an abstract, disjointed melodic line that conceals the chord sequence from Without A Song, and leaves room for a nearly continuous drum solo until the bridge”.

The leader’s bass and Davis’ drums fuel Hitchcock’s melodic saxophone inventions, and Davis is indeed a busy presence throughout as he delivers a series of sparky drum breaks in a series of exchanges with Hitchcock.

The sound of the leader’s unaccompanied bass introduces “Other People’s Dreams”, a composition of which Williamson states;

Beginning with a simple bass melody, a highly dissonant vibraphone arpeggio gives a clue as to where the piece might go. A looping chord sequence that never quite resolves supports the main melody, bass solo, and a steadily building development section, until the melody from the introduction reappears in a chaotic final section. The saxophone line here begins completely ‘outside’ (a G7 arpeggio over B major) but changes course into a series of sentimental melodic gestures that sit uneasily in their context”.

It’s another of those dark hued but hauntingly compositions that Williamson writes so well and it’s also a vehicle for his impressive ability as a bass soloist. The piece becomes more spiky and challenging as it progresses, with Hitchcock and Davis becoming increasingly forceful presences before the storm eventually blows itself out.

“2700 Q Street Northwest” was first drafted by Williamson and Immy Churchill when they were both studying at the Royal Academy of Music. Williamson says of the piece;

“The initially simple melody is inspired by ‘big-sky’ Americana, but modulates to a distant key in the bridge section before finding its way back home. An unaccompanied bass solo in the middle leads into a closing recapitulation in which the climactic key change goes a step further than before and the voice/saxophone melody reaches its peak. In the run of gigs and tours that lead to this album, sets would usually close with the final bass notes of this piece”.

Churchill’s wordless vocals float above Davis’ rapidly brushed ‘Last Train Home’ style drum groove, with the leader’s bass also providing rhythmic propulsion. Mansfield’s vibes then come to the fore, subsequently joined by Wilson at the piano and Hitchcock on tenor, with Churchill’s exquisite voice also coming back into the equation. The vibraphonist then takes a more conventional solo, before the momentum of the music halts abruptly, leading into that pensive unaccompanied bass solo. The brushed drum groove then resumes, signalling the other performers to get back on board with Churchill’s voice soaring, the piece eventually concluding with the sounds of the leader’s bass.

The title of “Gozo (Duo)” is self explanatory as Williamson observes;

“The final track was the last to be recorded, in an abbreviated vibraphone/bass duo form that is quieter and more contemplative than the other take”.

At a little over a minute and a half in length and performed on shimmering vibes and contrastingly resonant double bass it’s a brief but beautiful coda to a very impressive debut album.

In his notes Williamson rather underplays his abilities as a composer as he declares;

“Most of the time I thought I was just pretending to compose, but I was composing. A jazz bass player doesn’t necessarily have to write original music at all, so the existence of this album is a tribute to the friends and teachers who showed an interest in playing, hearing and developing what I wrote. What holds the music together is that each piece started from a melody first, and each expresses the belief that you can love a sound, an idea or a place and want to subvert it at the same time.”

I’m certainly glad that Williamson stuck with it and managed to get this music ‘out there’. His notes on the individual pieces may be highly technical but you don’t have to understand the theory to appreciate the music on an album that features some of the freshest, most stimulating and most enjoyable music that I’ve heard all year. Of course the presence of a stellar band helps and Hitchcock, Mansfield and Davis all perform brilliantly, with guests Wilson and Churchill also making excellent and telling contributions. The album is produced by pianist Nikki Iles, who does an excellent job alongside the engineering team of Ben Lamdin, Sonny Johns and Peter Beckmann.

But ultimately the triumph is Williamson’s as he impresses as both a writer and an instrumentalist. His bass playing is right at the heart of the music and he also establishes himself as a virtuoso soloist. Let’s hope that he can now take this music out on the road, I’d love to this material being performed live.

blog comments powered by Disqus