by Ian Mann

November 14, 2019

/ ALBUM

This is ‘chamber jazz’ with feel and spirit, evocative and intelligent music that embraces a broad range of emotions, as well as musical styles.

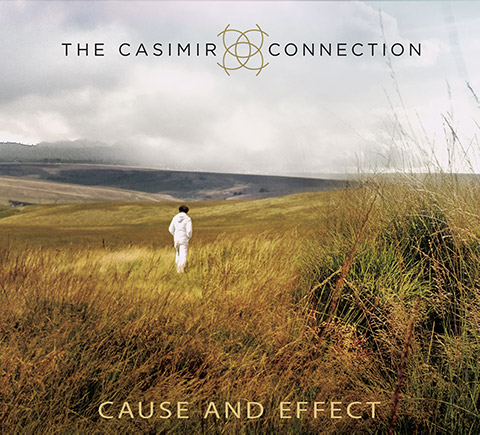

The Casimir Connection

“Cause and Effect”

(Ciconia Records 1910CD)

Diane McLoughlin – saxophones, piano, compositions, Pawel Grudzien – piano, violin

Kit Massey – violin, Tim Fairhall – double bass

When I first saw the name of this quartet I assumed that it was going to be a group led by the young rising star bassist Daniel Casimir.

On closer inspection I found it to be a new ensemble led by saxophonist, composer and occasional pianist Diane McLoughlin, featuring Kit Massey on violin, Pawel Grudzien on piano and violin and Tim Fairhall on double bass.

McLoughlin has previously featured on the Jazzmann pages as a member of groups led by bassist Alison Rayner and trumpeter Chris Hodgkins. She is a key member of Rayner’s ARQ quintet and has contributed compositions to the band’s repertoire. She has also written for Hodgkins’ groups.

The saxophonist also leads the seventeen piece Giant Steppes Big Band (great name), acting as musician, composer, arranger and bandleader.

McLoughlin explains her choice of name for this new quartet thus;

“The reference is to the Casimir effect, a mysterious force in quantum physics that draws elements together. I see it as a metaphor for the spontaneous energy created by musicians interacting intuitively when playing together.”

She continues;

“Cause and Effect is a journey through the influence of childhood experiences. The music sometimes reflects a mood, sometimes evokes a half forgotten memory, combining the sensibility of classical music with the instinctive spontaneity of jazz improvisation.”

Very much like Rayner McLoughlin’s writing is inspired by personal experiences and in this respect “Cause and Effect” is very much ‘an autobiography in music’. McLoughlin’s liner notes outline the inspirations behind each individual track, and in doing so they reveal much about McLoughlin, the person.

The music can perhaps best be described as ‘ chamber jazz’ and also takes in various folk influences as well as the aforementioned jazz and classical elements. And even though it’s a drummer-less line up there’s still plenty of rhythmic interest and impetus, thanks to the efforts of pianist Grudzien and bassist Fairhall.

Again like Rayner McLoughlin places great emphasis on strong and memorable melodies and there are some excellent tunes here in collection of eleven McLoughlin original compositions. Many of the pieces possess a strong narrative arc and a tangible sense of time and place – this is music that genuinely deserves the description “cinematic”.

Opener “Eisenstein’s Theory” was inspired by “a childhood memory of watching an old black and white film on television depicting Teutonic knights fighting Russian soldiers on a frozen lake. The image of the white horses and the defeated soldiers falling through the ice was a frightening and haunting image.”

Grudzien’s piano underpins the piece as McLoughlin on soprano sax and Massey on violin variously double up on and exchange melody lines. There’s an air of nostalgic melancholy about the music that finds expression in Massey’s bowing, but as its source of inspiration would suggest there’s nothing bloodless about this brand of chamber jazz, as exemplified by the leader’s expansive excursion on soprano.

“The Nurture of Nature” has more of a pastoral feel with McLoughlin observing;

“In a modern society full of noise and data overload, it’s even more important to have quiet times. Being outdoors surrounded by trees, grass and flowers, listening to birdsong, allows me to re-connect with myself. Nature soothes the soul”.

Almost classical in feel the piece includes some beautiful violin soloing, presumably by Massey, the bowing sometimes evoking the sound of birdsong or the image of a bird in flight. Piano and bass again provide the rhythm and structure around which the violin and saxophone swoop and soar. With the exception of McLoughlin’s reeds it’s difficult to credit individual soloists with both Massey and Grudzien credited with violin and Grudzien and McLoughlin with piano.

“The Secretive Irishman” was written for McLoughlin’s Irish grandfather of whom she says;

“he was a quiet man, but only later did we discover that his silence held many secrets. Family secrets can sometimes be a burden”. Behind these enigmatic remarks is an intriguing composition that embraces different elements of traditional Irish folk music. The first part of the tune has the feel of an air, wistful and nostalgic and distinguished by the gentle keening of McLoughlin’s soprano sax. The tune then gathers pace, evolving into a sprightly jig with racing soprano sax and violin melodies fuelled by propulsive piano and bass lines.

Of the melancholic “Lonely Child” McLoughlin remarks;

“Childhood for many can seem the most difficult times of their lives. Having a parent, or parents, who are suffering, especially from mental illness, can leave a child with confused feelings that are difficult to share, leaving them with a particular kind of loneliness”.

Musically the piece starts with the sound of Fairhall’s unaccompanied double bass, the sparseness and spaciousness of the playing seeming to embody the sense of isolation implicit in the title. Piano eventually enters, followed by sombre, but beautiful, violin, with Massey’s lines echoed and answered by McLoughlin’s soprano. Fairhall’s playing then returns to the fore in a glacial dialogue with the piano, this in turn leading to further saxophonic ruminations from McLoughlin. For all its beauty there’s a lot of pain in this piece.

“Up on the Moors” is a musical depiction of the Yorkshire landscape. McLoughlin and her colleagues conjure images of both beauty and bleakness in an arrangement that also captures the openness of the moorlands and, in the dramatic second half of the piece, its wildness.

As its title suggests “Torch Song” is a tune about unrequited love, but proves to be surprisingly lively, drawing as it does on the influence of Balkan folk music. There’s no piano here so the focus is on the interplay between the various strings, Massey and Grudzien are flamboyant on violins, while Fairhall provides the underlying bass pulse.

That Eastern European influence is also apparent on “Nadya”, which McLoughlin dedicates to the Bulgarian folk singer Nadya Karadjova. McLoughlin’s notes recount how she discovered East European folk music as a child, almost by chance on her transistor radio. “Suddenly the world seemed so much bigger and more exciting than the Yorkshire council estate I grew up in” she recalls. It was only years later that she found out that the singer she had heard was Karadjova.

McLoughlin features on soprano and Grudzien returns to the piano on this wistful sounding tune, the reflective moments punctuated by livelier ‘folk dance’ style episodes. There’s something of a feature for Fairhall on melodic double bass and an extended passage of unaccompanied piano, presumably from Grudzien.

“Lost in Colour” draws its inspiration from the twin sources of the artwork of David Hockney and childhood memory. A colour in a Hockney painting reminded McLoughlin of the “deep purple blue” of the paper bags that were used for currants or sugar during her childhood and of how she used to use them as drawing paper, or to create mosaics. Again the music evokes a nostalgic air as McLoughlin’s gently piping soprano intertwines with Massey’s violin lines. There’s an extended duo passage featuring bass and piano, Fairhall taking the lead at first before a more expansive and lyrical solo from Grudzien.

Of “The Storm Inside” McLoughlin says; “The internal world can often conflict with the external. There’s nothing comparable to feeling rage on a sunny day”. The dichotomy is expressed by a wilful dissonance, the harsh bowing of Massey, the low end rumble of piano and bass and McLoughlin making a rare foray on tenor – much of this album seems to feature her on the lighter, airier soprano.

“A Day in a Polish Village, 1933” reflects another side of McLoughlin’s heritage with the composer stating; “War not only causes physical damage, but mental damage too, which can last for years, even lifetimes. This composition is a tribute to my mother, who was a casualty of war. I knew little of her early life, but this is imagining of her as a seven year old child in a village in Poland”.

It’s a highly evocative composition that draws on folk and classical influences and features twin violins, with Grudzien, or maybe McLoughlin doubling on piano.

The closing “Contemplation” is a beautiful, lyrical, elegant ballad that wouldn’t sound out of place on an ECM album. This is particularly apt as “Cause and Effect” is immaculately recorded with mix engineer Grudzien, who also acts as McLoughlin’s co-producer, capturing every nuance and subtlety of the music.

The qualities that McLoughlin brings to ARQ are also apparent in this very different, and very personal, record. Her writing is consistently interesting and evocative and embraces a wide range of influences – jazz, folk, classical – that are skilfully woven together to create a very convincing whole.

This may be ‘chamber jazz’ but it’s music that transcends the sometimes pejorative assumptions that are made about the genre. There’s nothing bland or bloodless about this quartet’s music, and at no time did I find myself missing the presence of a drum kit. This is ‘chamber jazz’ with feel and spirit, evocative and intelligent music that embraces a broad range of emotions, as well as musical styles.

“Cause and Effect” is an album that McLoughlin can be justly proud of and it has enjoyed a highly positive critical reception, praise that will hopefully translate itself into sales.

blog comments powered by Disqus